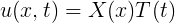

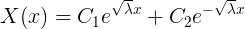

Starting from some definitions of the metric and normed spaces (here), we can start by defining the inner product spaces which will lead us to the Hilbert spaces.

We all know the scalar product from two (or more) vectors x, y ∈ ℝn:

This can be considered as an inner product for a vectorial space. As for the norm in a normed space, the inner product space (also named pre-Hilbert space) is a pair of a set of vectors and the definition of an inner product. The inner product on a space X is a mapping of X ✕ X into a scalar field K. We write the inner product as

An inner product must follow a set of axioms:

The third axiom refers to the complex conjugate. If both x and y are real, the inner product is commutative. For the forth axiom, it is equals to zero, only if x is the zero vector.

Remembering the definition of a complete space (from here), we can now define the Hilbert space as a complete inner product space. Hilbert spaces are Banach spaces with a norm that is derived from an inner product, so they have an extra feature in comparison with arbitrary Banach spaces, which makes them still more special.

Let's see now some properties of an inner product:

Remembering the definition of a complete space (from here), we can now define the Hilbert space as a complete inner product space. Hilbert spaces are Banach spaces with a norm that is derived from an inner product, so they have an extra feature in comparison with arbitrary Banach spaces, which makes them still more special.

Let's see now some properties of an inner product:

- Parallelogram equality: starting from the norm and with the axioms of the inner product, we easily reach to the parallelogram equality: || x + y ||2 + ||x - y||2 = 2(||x||2 + ||y||2)

- Orthogonality: when two elements x, y are in a space X, we say they are orthogonal if ⟨ x, y⟩ = 0. Also written as x ⊥ y

- Polarization identity: this helps us to get the inner product from a norm. Re⟨x, y⟩ = 1/4(||x + y||2 - ||x - y||2) and Im⟨x, y⟩ = 1/4(||x + iy||2 - ||x - iy||2). Those formulas correspond to the complex inner product, for a real inner product, only the first equation will remain.

- Schwarz inequality: remembering the triangle inequality, we have with the inner product, the Schwarz inequality: |⟨ x, y⟩| ≤ ||x|| ||y||

The projection, or orthogonal projection, is another concept commonly used in Hilbert spaces, but first we have to explain some other related concepts.

Let be a space X with an element x and a subset M ⊂ X. The distance from x to the subset M will be δ = inf ||x - y|| where y ∈ M. This sounds quite familiar, as it's the distance in an Euclidean space. But let me introduce more details to the previous definition to be sure of the uniqueness of y: the subspace M must be complete and convex for the solution being unique. This result can be easily demonstrate with the parallelogram equality.

Given the distance from the subset M to the space X, we get the vector z = x - y which is orthogonal to the subset M. Reordering the vectors sum as y = x + z we can see now that the vector y is the orthogonal projection of x on M.

Given the distance from the subset M to the space X, we get the vector z = x - y which is orthogonal to the subset M. Reordering the vectors sum as y = x + z we can see now that the vector y is the orthogonal projection of x on M.